“There’s so much uncertainty in life,” said Dr Teja Celhar, a research scientist at A*STAR, at the end of the latest public lecture held by the Humanist Society Singapore (HSS) on Saturday (Sep 28). “Knowing how some parts of life works – that is comforting to me.”

Most of us would recognise that deep human need to make sense of the world. Finding the answers to some of our most difficult questions, however, often requires a process that can be intimidating to even the most brilliant among us: science. But it need not be so. And in a world threatened by climate change and other potentially disastrous developments like the anti-vaccination movement, rarely have mankind needed to understand science more than now.

To help the average person in Singapore make sense of science itself, the HSS organised the lecture titled “Science, Pseudoscience and Fake Science”. Held at A Good Space at Clarke Quay Central with free admission to the general public, the event featured talks by Dr Celhar and Dr Robert Lieu, a lecturer with the National University of Singapore. Some 70 people attended the three-hour event, which concluded with a lively question-and-answer session moderated by HSS vice-president Tan Ding Jie.

The scientific method explained

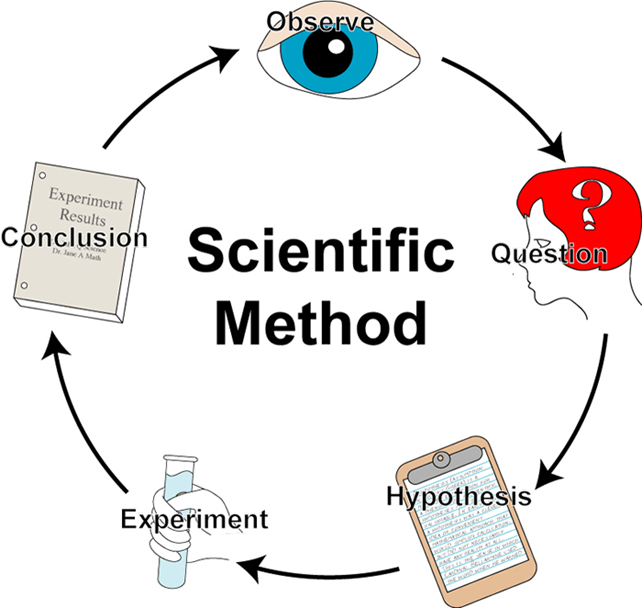

Dr Celhar, an immunologist, focused on the reliability of the scientific method, a continuous process of observation—question—hypothesis—experiment—conclusion—observation, and so on.

In practice, the scientific method as practised by scientists is a painstaking process that takes years before any result or finding makes its way to the general public by way of academic journals and media reports. It all begins, noted Dr Celhar, with a sound experimental design to test the hypothesis. What follows is a laborious process of collecting a sufficiently large and representative sample, and conducting controlled and randomised experiments whose results can be reproduced by the same or different researchers. Those results are then subjected to review by a journal editor then other scientists (“get used to being criticised”) before being published in an academic journal. Or not, in the case of studies that don’t pass the scrutiny of editors.

Dr Celhar, a mother of two, was only half-joking when she told the audience: “I think it’s easier to give birth to a child than to publish a paper.”

Science refers to the methodical way of gaining knowledge on a particular subject through observations and experiments.

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that are claimed to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method.

Scientists, therefore, regard fields such as homeopathy as pseudoscience, because they are incompatible with the scientific method. There is no scientific evidence that homeopathy works, said Dr Celhar, noting that it has been discredited by the authorities in the United States and France.

Yet, as rigorous as the scientific method is, it is not infallible, Dr Celhar said. Scientists have had to retract published papers due to mistakes or fraud; the breakthrough findings of today have been found to be lacking years or decades later. Nor can science explain everything, she acknowledged. But the self-correcting, continuous process of science is the “best tool” we have in our quest for answers. “Science can’t explain everything,” she said, “but it gives you something to help you understand a part of the human experience.”

The CRAP test

Knowing how science works is undoubtably useful for people who are endlessly curious about anything and everything. But what’s in it for everybody else?

Dr Lieu of NUS has a simple answer. “All science learners of today will become the consumers of tomorrow,” he said. “Students, the general public and other stakeholders must be able to evaluate any claim made in the name of science.”

That ability to “separate science from nonsense” is especially important in the age of social media, said Dr Lieu. Many of us would have experienced friends and family, not to mention marketeers, touting this or that product or treatment via Facebook or WhatsApp, based on anecdotal evidence or the recommendation of an authority who may or may not be legit. A healthy dose of scepticism, said Dr Lieu, and the ability to scrutinise claims would keep us from falling prey to misinformation, superstition or wasting money on dubious products. In some cases, such as decisions about vaccination or cancer therapy, it could even be a matter of life and death.

To put scientific claims to a litmus test, simply apply what Dr Lieu calls “CRAP”:

- Currency: How recent is the research behind the claim?

- How recently has the website been updated?

- Is it current enough?

- Reliability: Who conducted the research?

- Is content of the resource primarily opinion? Is it balanced?

- Does the researcher provide references or sources for data or quotations?

- Authority: How credible is the person who conducted the research?

- Who is the researcher or author?

- What are the person’s credentials?

- Who is the publisher or sponsor?

- Are they reputable?

- What is the publisher’s interest (if any) in this information?

- Purpose or Point of view: Is the claim based on facts or opinion?

- Is this fact or opinion?

- Is it biased?

- Is the researcher/author trying to sell you something?

- Are there advertisements on the website?

If the answer to any of the four questions is dubious, said Dr Lieu, the claim can be regarded to be not based on science or the scientific method. Otherwise, proceed to weigh the strength of the evidence cited by the claim by looking at the sample size and selection, and whether there is any confounding factor or researcher bias.

Dr Lieu noted that research outfits with names like Institute for Creation Research and Discovery Institute try to mimic how science is done. Using such words as “research” and “institute” in their names hint at an attempt at legitimacy.

“Whether or not they are on the right track, I don’t know,” said Dr Lieu. In science, he added, explanations must be based on evidence drawn from examination of the natural world. Scientifically based observations or experiments that conflict with an explanation eventually must lead to modification or even abandonment of that explanation. “Science is ever changing. Nothing stops here.”

Written by Li Shuhuai. Shuhuai is a volunteer at the Humanist Society (Singapore).