The year 2019 is the 200th anniversary of Sir Stamford Raffles’ founding of modern Singapore. On Darwin Day 2019, the Humanist Society (Singapore) invited Dr John van Wyhe to deliver a lecture on Raffles’ lesser known side – a naturalist in Southeast Asia. Dr John is a British historian of science, with a focus on Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, at the National University of Singapore. We have published a transcript of his lecture below:

By Dr John van Wyhe

It’s Darwin Day, but we’re talking about Raffles. Ordinarily, when one thinks about pioneering explorers and naturalists in Southeast Asia, usually Alfred Russel Wallace will come to mind, and quite rightly so.

But one should not forget that there were thousands of people contributing to the study of natural history in the past few hundred years or so. Raffles, it turns out, is one of them. And this is something that most people don’t know and cannot even imagine, because he is pictured as a statesman and various other things he’s considered to be.

Raffles as a Naturalist

A brief overview of the man himself: He was born in 1781 on the ship Ann off the coast of Jamaica, where his father was the captain. They were not a wealthy family and Raffles went to a modest boarding school, which he left at the age of fourteen in 1795 and started working as a clerk in the East India Company in London. It was through this company that, by 1805, he was sent to Penang and began his relationship with Southeast Asia.

Already, from his first station in Penang, he was pursuing natural history. He kept animals and he sent out collectors to gather more. In 1811, because Napoleon had conquered the Netherlands and the British feared that the Dutch East Indies would fall into the hands of Napoleon, the British chose to take over the Dutch East Indies .

Raffles was promoted way up the line to the role of the Lieutenant-Governor of Java, and then he began to pursue his natural history interests in earnest. Not only did he send home collections, he also kept two young tigers at his house, which I think shows that he was serious!

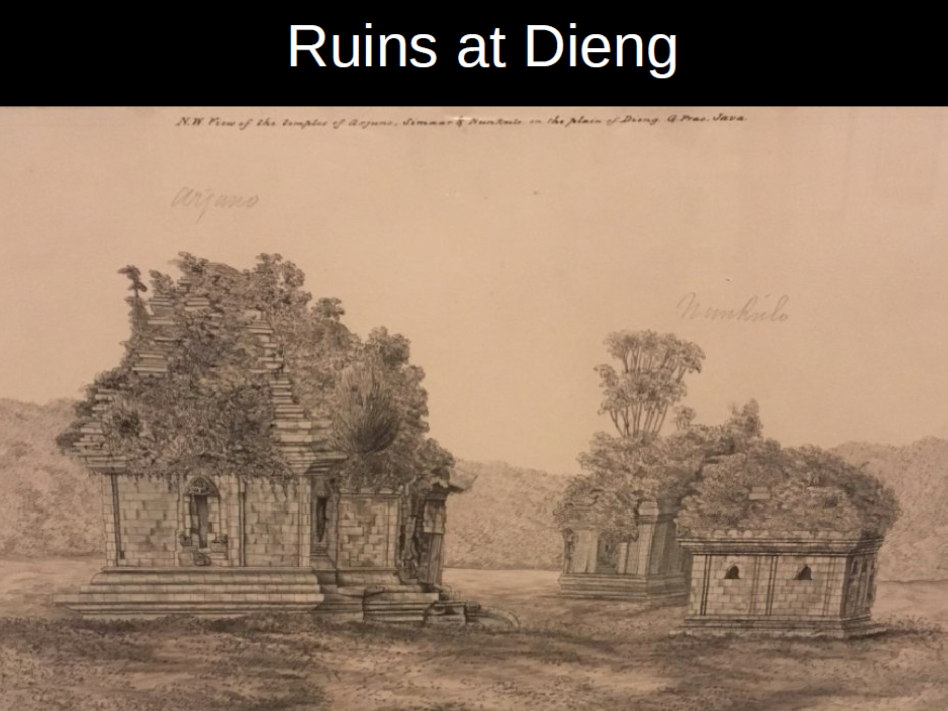

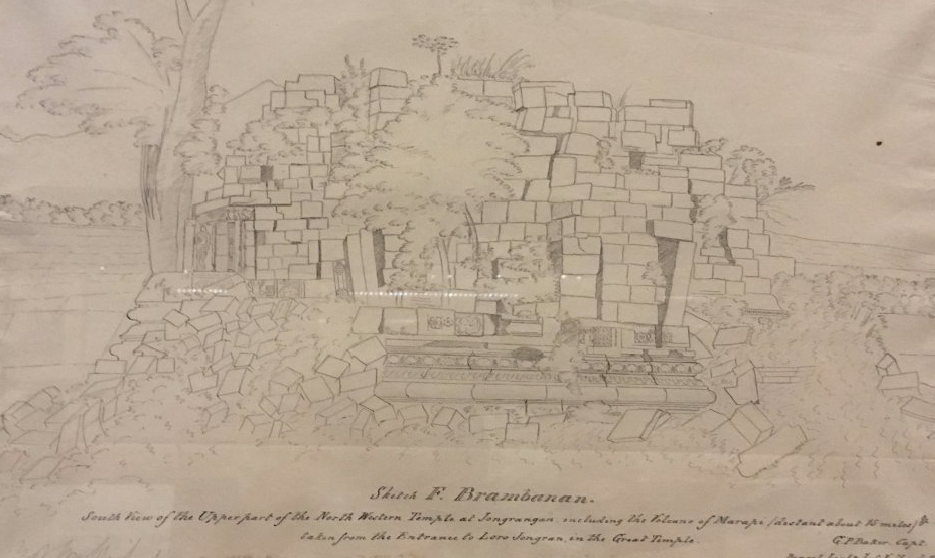

He also instigated the exploration, uncovering and partial restoration of some of the great historic monuments in Java. We have many of the sketches that survived from his team. The monuments were crumbling and overgrown. Raffles wanted them surveyed, sketched, and preserved as far as possible:

Ruins at Prambanan

These sketches, you can see, are in the Raffles Exhibition at the Asian Civilisations Museum right now.

Most famous of all is Borobudur. This photograph is from 1872, but it would have looked pretty much like this.

When you go and visit these monuments today, they look fantastic, they look great. That’s because they’ve been heavily restored, fixed, and repaired for many years. But in the state in which Raffles first had them uncovered, they were an absolute wreck. They were piles of stones in many places and the longer the trees and the vines grew on them, the more the stones were split apart.

So, he thought he was preserving these ancient monuments.

The other thing that he did for natural history, was that he promoted and sponsored some of the most important naturalists, especially botanists, in the region. Most notably, Thomas Horsfield, Joseph Arnold, and Nathaniel Wallich.

Now, in 1815, Raffles returned home and two years later, he published his big book — a two-volume History of Java. This is meant to be a comprehensive account, and it has an entire chapter on the geography and natural history of Java. Again, a central core interest of his gets in print.

Now it was this book which showed that he was not just an administrator and an officer of the company, but that he was a serious scholar, with more serious ambitions, great knowledge and learning. This led King George IV to knight him and hence, he became Sir Stamford Raffles as he liked to be known.

Return to Southeast Asia

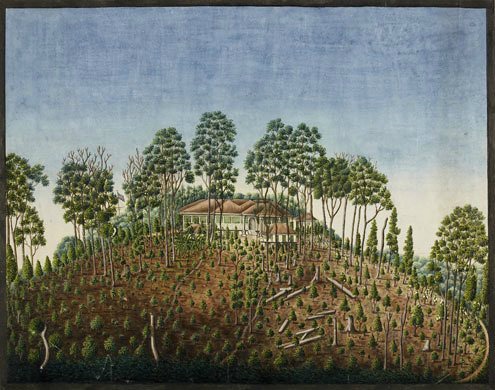

In 1818, he was posted again to Sumatra, this time as Lieutenant-Governor of Bencoolen. This painting of his house is also from the exhibition in the Asian Civilisations Museum.

But when he arrived back in Southeast Asia, in Sumatra, his colleague Horsfield wrote that:

In other words, now that he had free time as the boss, he wanted not only to pay for other collectors to go out, explore, and collect, but also to engage more actively himself than he had in the past.

Raffles himself wrote in 1820, (notably after 1819, a year which I won’t mention):

In other words, to the things Raffles already sent from his last posting.

He went back and forth, of course. During this time, he made another visit to Singapore in 1823, during which time there must have been a lot of collecting going on that we don’t know much about. However, his scribe Munsyi Abdullah wrote this detailed account of what Raffles was going to ship out when he left Singapore in 1823:

The sinking of Fame

In 1824, Raffles set sail again for England with the main part of his collection on board the ship Fame. Fire struck the Fame and ship was destroyed along with his entire collection. Thus, the results of thousands and thousands of man-hours of many people were lost.

Raffles wrote about this tragic loss:

It was all gone. What did he do? He returned back to Sumatra and immediately set to work, trying to build it up again even though it would be impossible to replace all that what was lost.

He had a team of Chinese illustrators whom he worked with everyday. Constantly, all day long, he would check on their work and accuracy.

These drawings can be found in the wonderful book Raffles’ Ark Redrawn. Their hand-coloured drawings included, but were not limited to, animals, birds, mammals, plants, nutmeg, and of course everyone’s favourite, durian.

These absolutely exquisite works of art as well as of science were fortunately preserved. You can see why Raffles said that “these were executed in a manner superior to anything I had seen in Europe.”

I’ll just show you a short collection that survived.

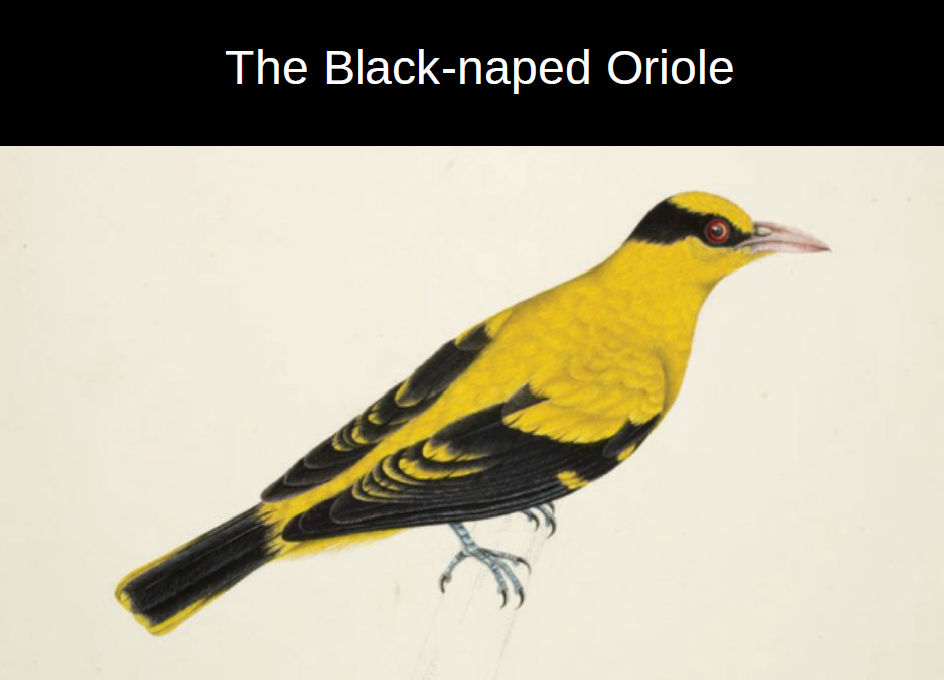

This one (below) will look familiar because it’s flying all over Singapore.

Aren’t they beautiful?

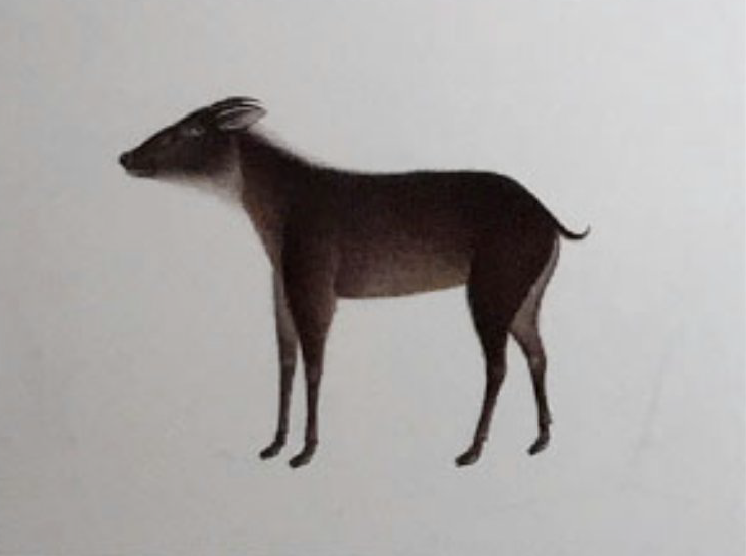

In addition to birds, there were several mammals. This is a sort of goat.

Then there’s the lovely Moon Rat and the delightfully charming Malayan Tapir.

You can see that the artist has taken great care. Note the cute little three toes there (above).

The drawings were not limited to animals. Plants too were illustrated extensively and beautifully. All were hand-coloured.

You can see why Raffles said that “these were executed in a manner superior to anything I had seen in Europe.”

In Singapore, you can see something almost identical to what I’ve just shown you in William Farquhar’s collection of natural history drawings at the National Museum of Singapore, which was exquisitely curated.

Patron as well as a practitioner

Farquhar is, of course, another big part of the Singapore story. I’m not going to talk about Raffles and Farquhar, thankfully. But the collection shows that Farquhar too had a serious interest in natural history, but it would seem nowhere near the scale of Raffles.

Perhaps he had nowhere near the resources of Raffles, because the size of one’s collection often depends on how many collectors one can afford to send out to collect specimens. But amongst these illustrations is one named after Raffles: Raffles’ malkoha. That is another exquisite drawing.

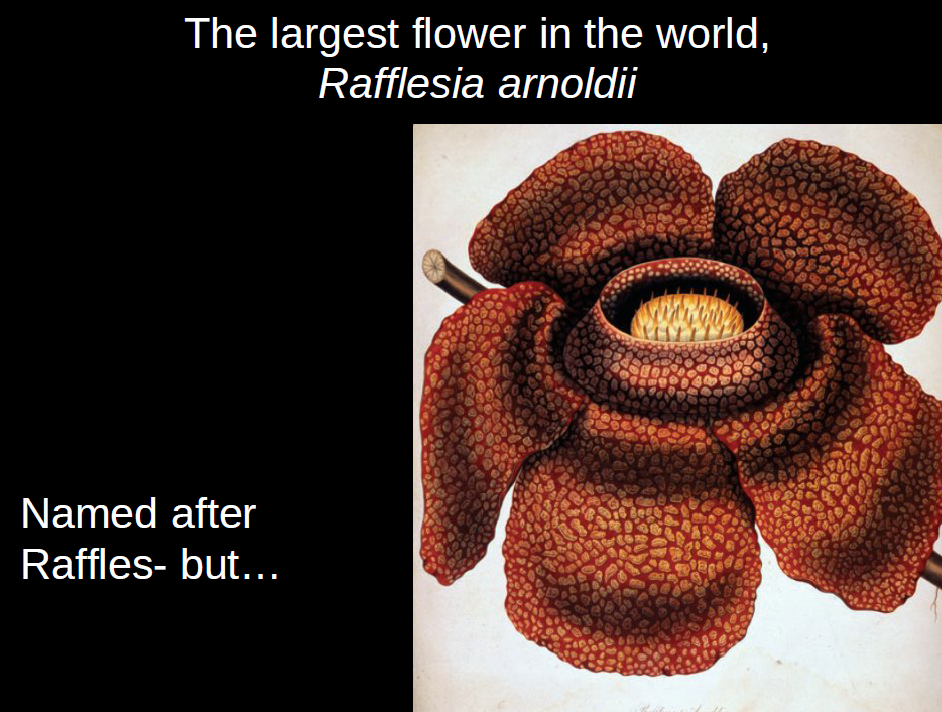

Raffles is particularly remembered in natural history for having the largest flower in the world named after him, the Rafflesia arnoldii. It is also the stinkiest in the world; I’m not sure if that also has to do with Raffles.

In any case, is it a dubious honour? I don’t know. Now there’s been a lot of discussion about this naming recently because the flower was collected by a Malay assistant but Raffles was credited with leading the expedition. People nowadays begin to question, is that appropriate?

Well, this is where I, as a historian, would like to step in and contest some of these opinions, because historical standards matter.

People in the past didn’t play by our rules. So, the local collectors were never or seldom credited or named. Credit would go to the person or patron who paid for a team of people to make the collection. This is why we have so many things in the world named after emperors, kings, generals, and so on. They didn’t do anything other than having paid for it. Alexander the Great did not build Alexandria, but it would never have existed if he had not directed that it be done.

Or perhaps, the patrons didn’t intend to be credited, but the person naming things after the patrons was just trying to impress them in order to get some patronage in the future.

It often works; it worked for Raffles with his book on Java. He got a knighthood. There is a lot of precedence for this. Wallace’s Standardwing, (below) a newly discovered bird of paradise named after Wallace, was actually discovered by his Malay assistant Ali from Sarawak, as Wallace himself told us in his book.

But no one, not even Ali, would have batted an eyelid at it being named for Wallace. That was the standard of the day.

I’ve been working on Wallace and his assistants in the Malay Archipelago over the last few years. I published a paper on it recently. I wanted to find out how many people actually assisted Wallace in his collections and research. Historical evidence is very incomplete, but as far as I can tell, at least 1,200 people assisted Wallace in building his collection during his eight years in the Malay Archipelago.

Raffles, in a way, is similar. He was a patron as well as a practitioner. He was very knowledgeable. He knew what he was talking about, but he also had the means to increase the size of his collection by sending out more and more collectors to find the sorts of thing he was interested in.

Raffles’ collections in Museums and Zoos

Many of these specimens collected “by” or rather “for” Raffles ended up in European museums as you can see here from the British Museums in 1845.

Museums. That was the place to go and look at beautiful things from faraway places, but where do you think all these dead animals came from? From collectors, teams of collectors, armies of collectors.

These specimens were valuable because it was extremely difficult and expensive to get to the other side of the world. 99.9999% of those people would never see such distant parts of the world.

Today, we are spoiled. With the internet, television and colour photography, we can see beautiful things from all around the world whenever we want. But it wasn’t possible in the past. Someone had to either make a drawing or painting or bring actual examples of dead ones and occasionally live ones back from far away.

So Raffles, whom we remember as this towering white statue figure connected with Singapore, had another legacy after he returned home to England in 1826. He wrote in a letter:

“I’m much interested at present in establishing a grand zoological collection in London with a scientific society for the introduction of living animals.”

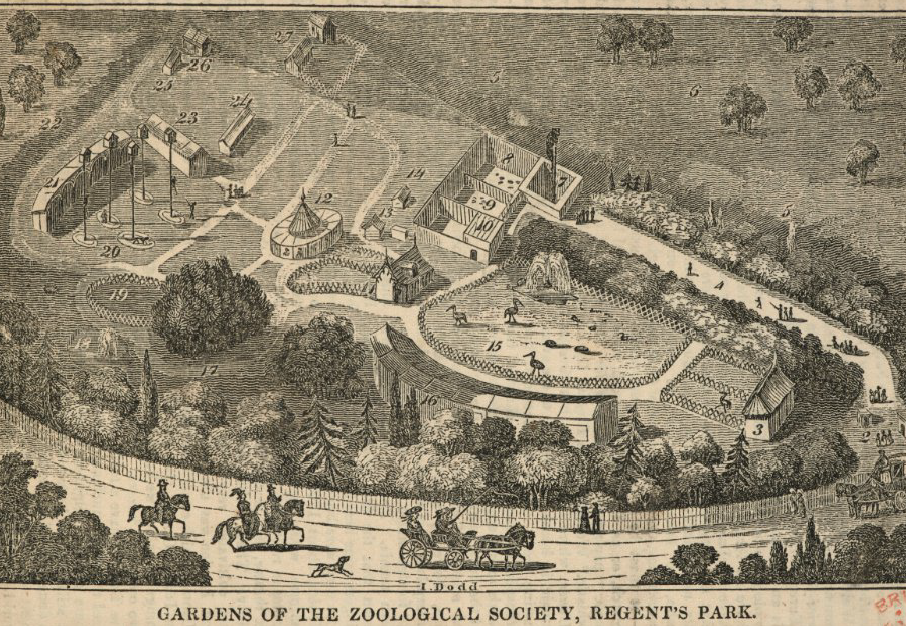

The Zoological Society of London was founded in April 1826 by Raffles and a few others. Raffles was appointed its first chairman and president. Why him, of all the people who had been patronising it? Because he was the driving force who wanted this to be done. And he wanted the Zoological Society to have a garden.

We’ve shortened “Zoological Gardens” to what we now call a “zoo”. But that’s where the word comes from.

Not long after, in July 1826, Raffles died unexpectedly. But his dream of a scientific institution to study the natural world was realized.

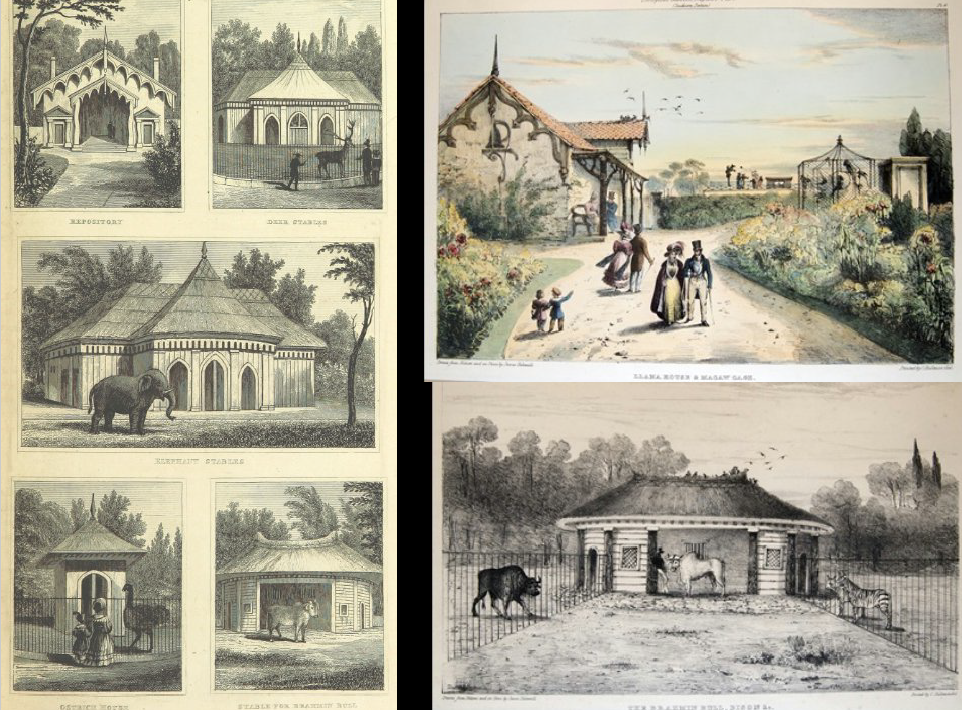

Here is an early diagram of the Zoological Gardens.

See the way they described the Zoological Society Gardens of Regents Park.

The Zoological Society has a plaque commemorating the fact that he was the first president of the society.

So, the zoo in these early days looked something like this, which I supposed won’t look very zoo-like to you.

It wasn’t very zoo-like in our terms. The society’s gardens were only opened to Fellows of the Society; they were not opened to the public until 1847. They were intended for serious scientific research; they weren’t there to entertain or to educate the public. They were there for serious naturalists and Fellows of the Zoological Society to study animals, their behaviour, their anatomy, and so on. Nowadays all this would be illegal because they didn’t have enough room and so on.

Here is an enclosure with bears. There’s a bear on a pole. He lives in a big pit. There’s a big wooden pole which the bear could climb up to look at the visitors. Here are the visitors with sticks either taunting the bear or feeding the bear with some bread.

It was acceptable to do that in those days apparently. Of course, the London Zoo has somewhat modernized since then, but not all of it.

This is the giraffe house. It is the oldest zoo building in the world still being used for its original purpose. Now what is special about it was not just the fact it had really tall doors. It was heated. This allowed animals from warmer climates to be kept alive in the colder climate of southern England. This heated giraffe house is where I have a surprise for you.

Raffles and Darwin

Since it’s Darwin Day, I thought I would unveil a connection between Raffles and Darwin.

So, Raffles established the gardens and this heated giraffe house, but it didn’t just house giraffes. It housed lots of other kinds of animals that would die if they were left out in the cold.

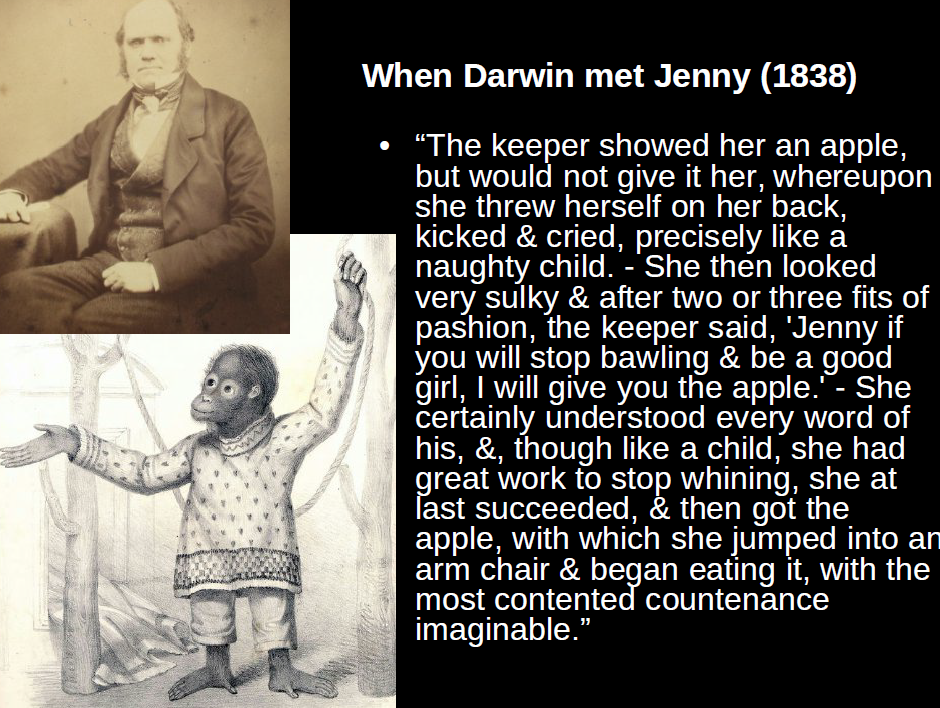

These included orangutans. One of these was famously known as Jenny. So, I’m going to tell you a little bit about when Darwin met Jenny.

In 1838, Darwin, who as a Fellow of the Society could go in and interact with the animals (not like today where the animals were behind bars), wrote this letter to his sister:

So, Jenny was happy there. But Darwin wasn’t there simply to amuse himself by watching the orangutans. He was there for research purposes. Darwin, of course, was just starting out on his theory of evolution in 1838 and he had gone to see Jenny as the only possibility of seeing a living great ape. By this time he already believed that the great apes were our closest living relatives.

By observing Jenny, he thought that he could find clues as to what we might have in common with them, and what we might not have in common with them. He described them in very anthropomorphic or humanlike terms: after all she’s got clothes on. To amuse visitors the keepers would have them drink cups of tea, sit in chairs and things like that. Yes, it is anthropomorphic.

But with Darwin, I think, we shouldn’t go quite so far as to call it that, because it isn’t anthropomorphising if you believe both you and them are almost the same by descent. He’s not mistakenly attributing human characteristics to his dog as most of us do, or to your cat, such as saying “my cat loves me”. No, he doesn’t; he’s just hungry.

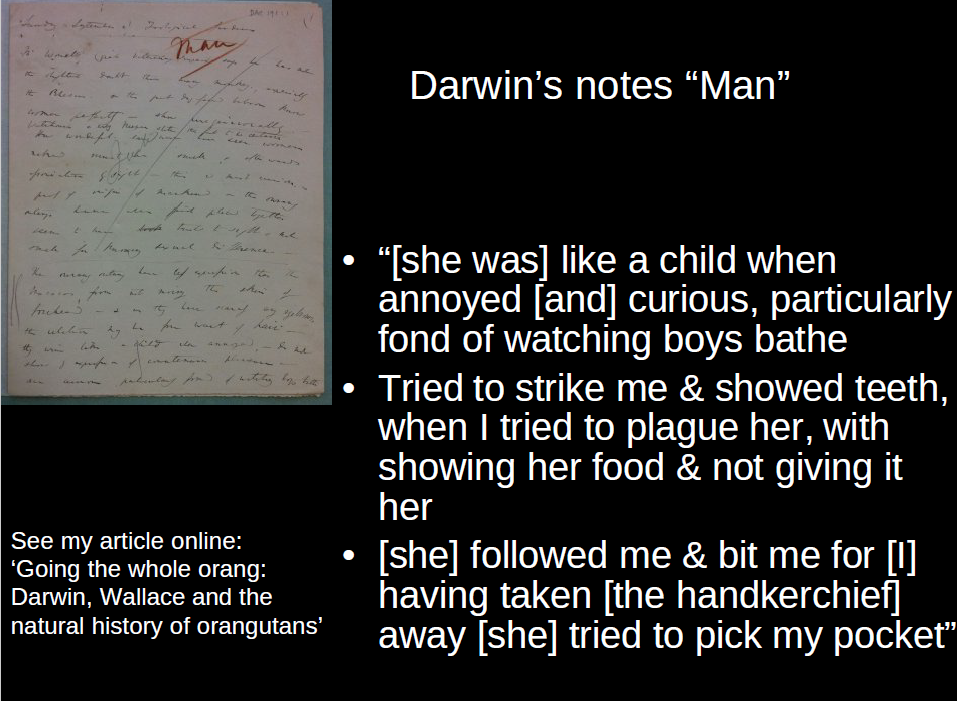

A cat is quite different from a human, but an orangutan or chimpanzee is very similar to a human. Darwin was looking for these evolutionary links, so what I’m going to show you next is the few sheets of paper on which Darwin took notes when he was with Jenny:

These notes remain in the Darwin’s Archive in Cambridge University Library which I published for the first time a couple of years ago. I’ll just read you a couple of extracts which I think will surprise you about Darwin’s interaction with Jenny:

First of all he calls the notes “On Man”. They are not characterised as orangutan notes; they are categorized or filed under the subject of mankind. He goes on to say:

So he was taunting her and teasing her by not giving it to her, he wanted to see how she would react.

“Finally she followed me and bit me for having taken the handkerchief away and she tried to pick my pocket.”

This is a new revelation that Charles Darwin almost had his pocket picked by an orangutan.

Issues with the film Creation

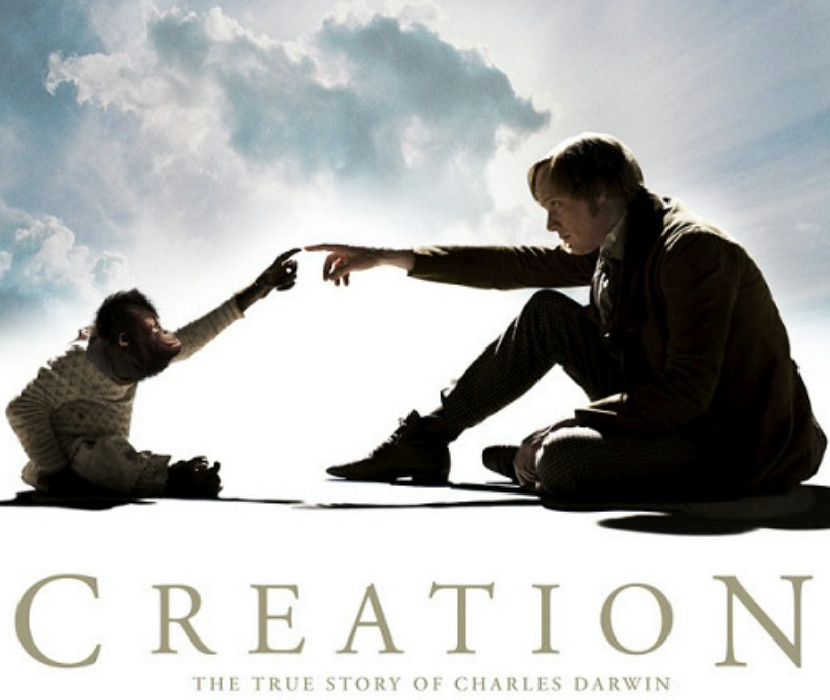

This meeting of Darwin and Jenny has become quite famous particularly because of its role in the 2009 film Creation. There it is: the movie poster as well as the soundtrack.

Paul Bettany plays Darwin touching fingers with Jenny which is of course reminiscent of the famous fresco on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel where Adam and God almost touch fingers.

The problem is the subtitle of this film Creation, “The True Story of Charles Darwin”.

I’m sorry to say that it is a little bit inaccurate. The only things true in this film are the names of the people. There really was a Charles Darwin, Emma Darwin, Huxley and a Jenny and so on, but everything else in this film is entirely fictitious.

Everything in it revolves around a made-up conflict between Darwin’s and his wife about religion and his theory. There was no such thing. There is a scene in which the actor playing Huxley tried to encourage Darwin to publish his theory and he says “You’ve killed God, sir!” He said it twice actually. No, Huxley never said that and he didn’t think like that.

Photo: Dr John delivering the Darwin Day 2019 lecture.

But by projecting this fake story to a modern audience, it makes it more difficult for people to accept evolutionary theory. It was easier for the Victorians, because they weren’t so bound up with these fake camps that we think the world is divided into: the religious people and the scientific people (or the secular people).

In fact, most people back then were both (religious and scientific people), as it is with Raffles.

So, with that, my story comes to an end.

Thank you very much!