Written by Vanessa Ng

Starting anything from scratch is no easy feat, and building a community from ground up is hard work. So why did Yi Ming choose to do both amidst piling school work as an undergraduate in Yale-NUS College? Even as a current master’s student in Urban Science, Policy and Planning at the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) and an aspiring sociologist, he continues to contribute to the brainchild created a couple of years ago.

Keen to find out more, I met the 25 year old over video conference. The background noises were loud, with random airplanes zooming off every now and then, almost mocking how we are both stuck in Singapore thanks to the Omicron variant.

The Why: An Impetus to Start

The founding co-president of Humanism, Yale-NUS, Yi Ming believes strongly in exploring Humanism as spirituality beyond religion. “Note that I said ‘beyond’ and not ‘without,” Yi Ming emphasized. “Humanism draws on the vast plurality of human wisdom, of which religions are a key source, that it isn’t fair to constrain it.”

To understand his personal impetus for kickstarting the college society, we will first need to look at what happened in Amherst, Massachusetts.

In 2019, Yi Ming spent a semester abroad at Amherst College. An American liberal arts college which prepares critical and creative thinkers for lives of purpose and discovery, the school has an unsurprisingly diverse representation of various communities. Curiosity and interest led Yi Ming to join the Amherst College Humanists. There, he found joy in talking about secular philosophies and spirituality with fellow like-minded individuals.

Growing up non-religious in a nominally Buddhist family and catholic primary school, Yi Ming saw the value of religious institutions in providing key spiritual and social support to their respective communities. In this regard, the non-religious are comparatively underrepresented and underserved in Singapore. For one, the general public awareness about the concept of Humanism or secular spirtuality is low here, and spirituality tends to be a personal, or even unexplored topic amongst the non-religious.

Over at Amherst College, however, Yi Ming experienced for himself the value of sharing and celebrating meaning in our lives through deep and intellectual discussions with fellow Humanists. After all, where can the non-religious turn to when they face challenges with their spirituality in everyday life? Where can these people share common grievances of being non-religious, when there is no community to do it with?

“In a sense, we are a marginalised community.”

The What: Growing Communities

While religious groups can fall back on main texts, long-standing practices and fellow believers, how can the non-religious seek guidance?

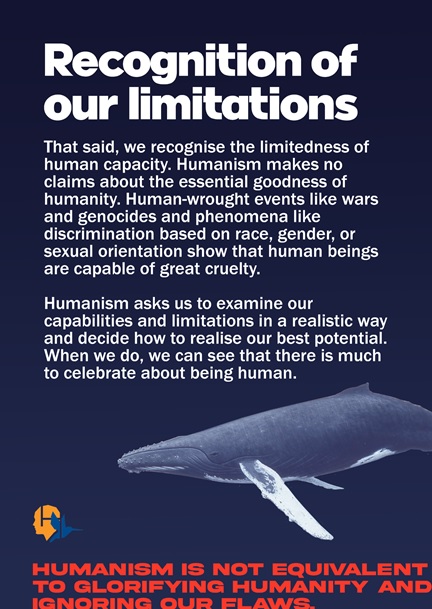

Humanism is exceptionally tricky in this regard as there is, intentionally, no central body of text. Rather, various Humanist associations around the world have agreed on certain fundamental principles and philosophies. Beyond these fundamental principles, Humanists are entitled to explore their specific philosophies on life through research and contemplation. This is not to say that there are no Humanism resources online – there are plenty. It is up to the keen individual to dive into.

Through all these writings, videos, podcasts and more, across the diverse Humanist associations and philosophers around the world, a Humanist is free to contest the philosophies of Humanism and to search for their own definition of a life well lived in line with their individuality, as long as the fundamental Humanist principles of enabling the collective flourishing of all are adhered to.

From what Yi Ming shared, Humanism.Yale-NUS seems to adopt an inclusive take where Humanism is not strictly secularism, and can be viewed as relevant or possibly complementary to religion.

The club has three simple focusses – to provide a spiritual community for the non-religious, a safe learning space to advance a humanist way of life, and to act as a bridge connecting diverse human knowledge and lived perspectives.

Together with his co-founder, Yi Ming conceptualised two pillars of society initiatives – Humanism and Humanity.

Under the Humanism wing, one of the things that students can partake in is monthly dinners to discuss various core themes of Humanist thought, such as the nature of reality, knowledge, meaning, morality, and collective responsibility. The discussions are organic and lively. It can start with a casual conversation on how humans are only human, before delving deeper into the idea that our knowledge is not infallible, can always be re-evaluated through empirical reasoning, but that worldly uncertainty is ultimately empowering, as it opens the door to curiosity and discovery. The discussion sometimes goes a little off track, and often explores applications such as new ways to live in the 21st-century. Such is the open-mindedness of the community – free of judgement and open to discussion.

Humanism.Yale-NUS infographic on recognising our limitations

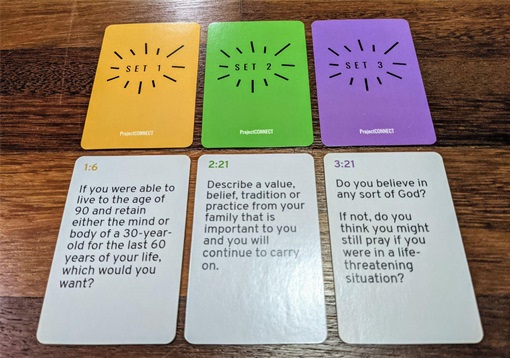

The second wing is the Humanity wing, which is open for all, Humanists or otherwise. I find the inclusivity worth applauding and truly representative of a liberal arts school. An example of their flagship event is ProjectConnect, which connects the entire college with students from the broader NUS University Town, to reduce prejudice and allow people from different residential communities to interact. Participants discuss a series of thought-provoking questions and complete mini community-building projects.

All these frameworks and events are meaningful in cultivating and building the Humanist community. Yi Ming even shared that he may consider working with the Humanist Society Singapore to share some of these learnings and bring some initiatives to the national Humanist community.

While sharing the activities, Yi Ming expressed his regret that physical group activities were disrupted due to the pandemic, and that the longer-term development of the society is left uncertain by the college’s impending closure.

Some of the thought-provoking questions discussed during ProjectConnect

HSS talk at Yale-NUS on Humanism in Singapore, September 2021

The How: Overcoming Difficulties

When asked about what challenges were faced, Yi Ming was candid in sharing his sentiments.

Since Humanist spirituality is largely a novel concept in Singapore, it can be tough to convey what Humanism is to potential participants or members. It does not help that Humanism is so plural that condensing it into a simple one or two liner will not do it justice. Yi Ming did not want to risk misrepresenting Humanism.

To circumvent this, Yi Ming gives out a comprehensive information sheet on Humanism and what the student club focusses on. Unlike other brochures selling the positive points of a product or service, this information sheet is truly a non-obligatory invite for recipients to see if they identify with the society’s principles and initiatives, and to find more if they are interested and comfortable.

The student club now has over 50 members subscribed to their mailing list, with over 100 likes on their Facebook page. While the number may seem unimpressive, it is important to note that Yale-NUS has just slightly under 1,000 students.

The Who: Marginalised secular community

On hindsight, Yale-NUS is perhaps an ideal place to incubate a Humanist student club. As the first liberal arts college in Singapore, all students start their first two years with a Common Curriculum introducing the world’s philosophical, political, sociological, and literary thought, from ancient Hindu epics written more than 2000 years ago to a 21st-century Singaporean political comic. Armed with a strong background on humanity’s great texts, students are knowledgeable and ready to discuss worldly issues that Humanism is concerned with, that is, if they want to.

Fellow non-religious school mates of Yi Ming feedbacked to him that there were occasions where they felt uncomfortable and conflicted when approached by some religious acquaintances. At that time, they were not ready to handle how vocal and outspoken their friends were with their beliefs.

“It can be quite destabilising and devaluing for them. During such interactions, not being religious implies an inequality, as they are seen as lacking the privilege of a personal affiliation with a higher being.”

A few school mates shared with Yi Ming on how they received judgement and were implicitly deemed to be spiritually inferior, just because they were non-religious. “After attending our dinners, some members told me that they now realized that Humanism.Yale-NUS was the secular spirituality community they needed back then, for crucial community support against discrimination.”

It is comments like this that keeps Yi Ming motivated to improve on the student club. It is imperative for him to recognise and support marginalised communities like the non-religious. They should be entitled to perceive their reality and see their self-worth in a secular context should they choose to.

“There is a lot of room for the non-religious community to think about bigger questions and find meaningful interactions. We all have questions about life, we wonder why we are here, and what we should work towards.”

“Humanism invites you to answer these previously deprioritised questions at the back of your minds. There are rich answers out there waiting to be discovered, and many more new questions to be asked.”

Through the self-discovery process, I am sure that Humanists will learn more about themselves and be well-equipped to answer new questions of tomorrow.