As part of our #HumanismAtHome initiative, we held a Skype group chat (‘Skype Party’) on May 9 (Sat), discussing food security in Singapore. It was an informative and highly engaging discussion lasting 1.5 hours. A local farmer in Singapore, Ms Eng Ting Ting from Urban Farm and Barn, joined us and shared her experience as a microgreens farmer.

Background

Photo: Orchard Road used to be an orchard plantation, hence its name.

Although food is a key part of Singapore’s national identity and a unifying cultural thread, Singapore allocates less than 1% of land to agriculture, down from around 20% in 1965 where most of the island was covered with plantations, pig and chicken farms, and some small fishing ports.

As one of the smallest and most densely-populated countries in the world, agriculture took a backseat upon independence as land was prioritised for industries, business parks, public housing and defence needs. Today, the city-state imports up to 90% of its nutritional needs.

The circuit breaker – Singapore’s equivalent of what’s commonly called a ‘lockdown’ – in response to Covid-19 pandemic has sparked some panic buying in Singapore’s supermarkets.

Even as the situation stabilised with support from national stockpiles and increased imports from other countries, certain types of food products remained scarce in supermarkets due to disruptions in the global supply chain.

Hence, it is a timely period to learn more about food security in Singapore, What role can local farmers play in ensuring this security?

The Skype discussion

During the Skype, we were happy to learn about Ting Ting’s experience at Urban Farm and Barn.

Located in Bukit Panjang, the farm grows microgreens, young edible greens produced from vegetables, herbs or other plants. In addition, the farm also hosts workshops for schools and companies. A snapshot of some of the microgreens grown:

Photo: Images from Urban Farm and Barn Facebook page

The following points were raised at the Skype discussion. Names were withheld to protect privacy and also to ensure adherence to Chatham House rules. These points also do not represent the official view of the Humanist Society.

1. Singapore’s land is more expensive compared to the region

- This comes as no surprise given Singapore’s size. Farmers have to think of ways to make vegetables grow faster, so they can harvest more often.

- Farmers also need to grow higher value vegetables. You cannot make much money growing conventional vegetables.

2. Locals need to be willing to support and buy local produce

- Local farmers are constantly worried that the market will not absorb extra produce.

- Consumers naturally gravitate towards cheaper alternatives in the market.

- Perhaps businesses and importers can give priority to or increase support for local farmers, and reduce parallel imports.

Photo: A rooftop farm in Raffles City

3. Urban farms are not that easy to manage, and don’t yield that much

- While roofs could be used for farming, they are not purpose-built for farming.

- This means there are limits to rooftop farms given the infrastructure limitations e.g loading/weight restrictions on roofs, the lack of proper lift and access, proper water and waste management systems, prohibition of drilling and erection of permanent structures etc.

- Lifts often do not reach roofs where the urban farms are located. Carrying heavy things (soil, tools, harvests) to/from the roof is physically exhausting.

- Yield studies and statistics collected on small-scale urban farms shows that the yield is not that great when compared to a high-tech farm.

- However, urban farms are useful when it comes to capability building, such as educating people about basic growing and farming skills.

4. It is quite hard to grow your own crops at home

- Discussion participants who tried to grow their own crops at home, found it quite a messy challenge.

- It is not about growing once and harvesting the crop, but about sustaining the mini-farm over time and enabling a reliable harvest over time.

- Growers have to be careful that they are not spending more than they would be if they bought the produce directly from the market.

5. Ensuring a reliable food supply depends on an entire logistical ecosystem

- Uncertainty caused by Covid-19 makes it difficult for farmers to decide how much to grow in advance.

- If the circuit breaker does not end, restaurants cannot open. Then, there will be no demand for certain farm produce.

- If there is a sudden surge in demand, farmers need time to grow their crops.

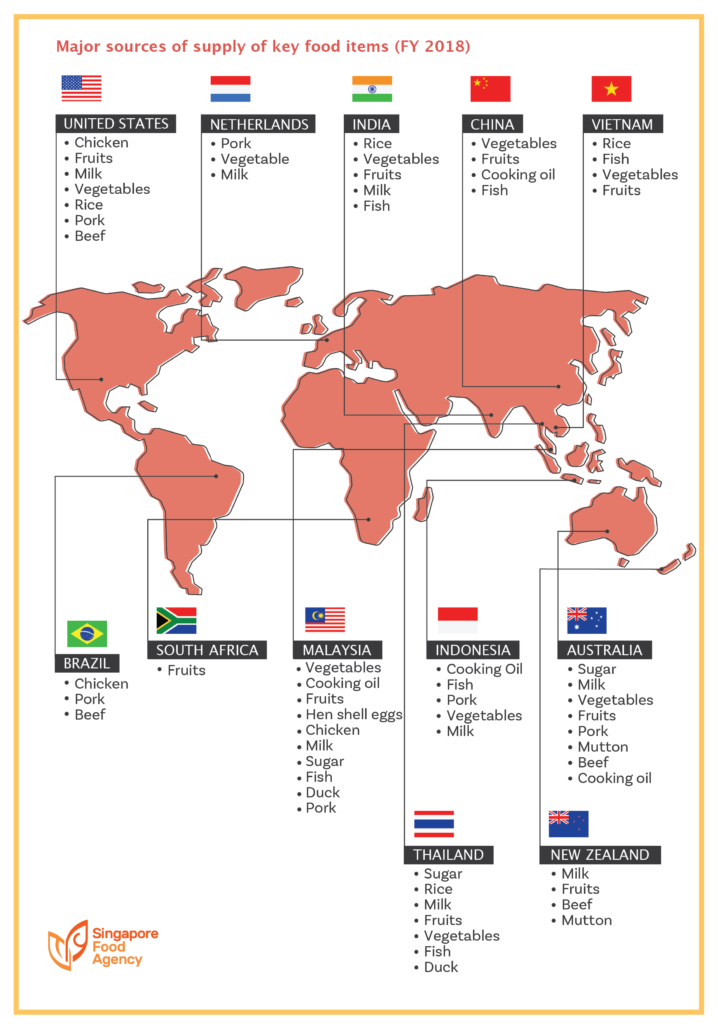

6. Singapore’s food supply is already highly diversified

- Singapore imports more than 90% of its food from about 170 countries and regions. Check out this cool graphic from Singapore Food Agency:

Conclusion

There are no easy answers to Singapore’s food security. It is not a question of simply ‘growing more’ locally. A land-scarce and densely populated country will always find it not cost-effective to grow its own food supplies. Local consumers also need to support local produce. Although no country can achieve 100% food security, Singapore has already taken great care to diversify its food sources over the years.